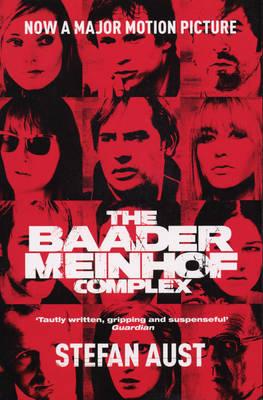

Middle-class terrorists: The Baader Meinhof complex

May 2009

How did a bunch of middle-class student activists end up in a web of international terror and murder?

How did a bunch of middle-class student activists end up in a web of international terror and murder?

Stefan Aust, journalist, commentator and former editor of Der Spiegel, has spent his career finding out, saying his book The Baader Meinhof complex was a once-in-a-lifetime case of a "story looking for an author".

The book examines in gripping detail the lives of a group of German revolutionaries known as the Red Army Faction (RAF). They began as student protesters against war and the state in the sixties and ended up committing arson, bombings, murders and kidnappings. In prison they went on hunger strikes, and won widespread sympathy when the authorities force fed them.

Some of the of the group died in prison - there were questions over whether it was murder or suicide, and how the prisoners managed to do it. Two had shot themselves, one had hung herself – even though they were closely guarded, no-one heard the shots or found them until the following morning.

Dramatic story

At his Auckland Writers and Readers festival session with Mark Sainsbury, Aust decribed this chapter of German history as “the most interesting and dramatic time after the Second World War”.

The power of the government was really threatened – most of the people who experienced that immediately raise the same questions – but the sympathy has vanished. People see them more as crazies, trying crazy things

, he said.

Revolutionaries were pop stars at that time – they played the role of mini Che Guevaras – a lot of people admired them. If you read Dostoevsky one hundred years before there are some similarities.

The more I dive into the subject the more interesting it gets – the details – the letters, the secret service, the bugging, the judges reaction to Ulrike Meinhoff when she asks:

How can a prisoner show the authorities that he has changed his position?

She repeated this over and over – the judge stopped her. She publicly tried to get out of the group – it would have been the end of the RAF but nobody knew that.

- I began by asking Aust how much research and source material he had collected.

- “Because I knew some of the people for a very long time - from before they went underground – I spent a lot of time with that scene where it all came from. When they went underground I was working for public television and had to do a lot of films, documentaries, magazine-style pieces, so I was very close to these events for a very long time.

“Then in the beginning of the 1980s I decided to write a book about it so the first thing I did was collect files. I got almost all the files that were used in the trial. In my apartment I had something like 60 metres of files and I read them all page by page. So I used, let’s say, the whole German police helping me in the research – that’s how I got so many details. - “When I was working in TV I collected a lot of stuff at that time. When I started writing the book it took me about three years – I didn’t do anything else. I spent years and years with that subject.

- One of the striking aspects of the book for me was the tremendous courage you showed uplifting Ulrike Meinhof’s two children from Sicily. Was it a snap decision?

- “It was an adventurous time, actually. I didn’t think twice. I knew from a friend who was in the guerrilla camp in Jordan, what they were planning to do with the children. We discussed it a lot. We said it’s impossible to let them do that if we can intervene. We didn’t see a chance. But then we met a girl who was involved in bringing the children to Italy, who knew the code word, the telephone number and everything. There was a window of opportunity and I said I’m going to do it – pretend to be one of the group and pick up the children and give them back to their father. Actually I think anyone would have done that. I was a young journalist at the time. I didn’t plan to write about it, and I never wrote about it until 15 years later when I wrote the book. It was an adventure.”

- Was there recrimination from the group – were you in personal danger?

- “Oh yes. When they came back from the Middle East and they sent somebody down to Sicily to pick up the kids and the kids were gone – they wanted to send them to some orphan’s camp in Jordan and make young guerrillas out of them – they tried to find out who it was. They were standing outside my door in the middle of the night and wanted to shoot us. We were warned and we had a very narrow escape. It’s not very funny, but it’s so many years ago it’s not true anymore.”

- Were there ever allegations that you were involved with the group as a conspirator? How did you maintain a journalist’s distance?

- “Even when I was working for konkret during these strange left-wing radical times from '66 to '69, I was always a journalist standing at the side, watching, writing and making films about it. I was never really a political activist, at that time or later. I never really had a problem with that, even when I was working for public television there was never any connection between me and terrorism. The opposite, because a lot of people knew after I wrote the book that they almost killed me. That was rather good proof.”

- There was an amazing amount of sympathy for this group. Do you think that kind of middle-class with a cause terrorist group could rise again? Do people believe in those political causes quite so much these days?

- “I think there is no terrorist movement without a big, radical base. There are no terrorist groups that are like islands somewhere in the ocean. They always have friends and sympathisers who wouldn’t be willing to go underground to throw bombs. The students movement, the radical movement - it was a time when a lot of people identified with revolutionary movements all around the world. Although they were not willing to go underground or to go to South America or to pick up the gun they were very sympathetic to people who would do that.

“That changed quite a lot after they started their underground war and killed people and threw bombs, but then the sympathy in a certain way came back when they were in prison, when they were victims themselves, then dropped away again.

“That changed quite a lot after they started their underground war and killed people and threw bombs, but then the sympathy in a certain way came back when they were in prison, when they were victims themselves, then dropped away again.- “If we had a radical movement like that again it could happen, but I don’t see it now. The radical movement which you can see in the world now which is comparable is the Islamic movement and not every Islamist is ready to throw bombs, but inside this huge group in the world there are enough people who do it. Even in Germany now we have a trial no against one of these Islamic groups who planned big bombings, and there are two German members – sons of middle-class families like those of the Baader-Meinhof group at the time. If you think back thirty years they would certainly be members of the Red Army Facation or other similar groups.”

- The process of making a movie you have the opportunity to create a new events like fiction writers do, but you didn’t do that. I read that in one scene you used the same shirt that was worn by one of the members in the original Vietnam Congress – how else did you accurately recreate history in the film?

- “We tried to stick to the original story, because it’s very hard to invent a story as exciting as the real one. It wasn’t necessary to do that, so we tried to reduce it. If you compare the original version of the book in German it is 900 pages – the amount that’s been shown in the film is about 100 pages – you can imagine how much we had to drop.

- “But we wanted to use the real elements of the story, we wanted to concentrate on the why and how these people went from protest to violence to terrorism, and we wanted to show it with the main characters – Baader, Meinhoff and Ensslin. We had three characters in a time of ten years.

“The only thing we had to artificially construct and add were I would say bridges between the original events. Some dialogue that makes you understand what was going on. As far as possible we tried to stick to the real events – the real shirt. When you see the dialogues in prison, they are reconstructed from the letters they sent each other. When you see the trial – it was shot at the real courtroom, we had the chance to use it for five days and what those people say [on screen] is word by word what they said in the real trial.” - There’s been several editions and a movie – do you think you will turn to a new project now – or is it too much part of your life to let go? You couldn’t do another story like this could you?

- “No I can’t. In this case it’s not an author looking for a story but a story looking for an author. This probably happens to you once in your life that you are so close to a story and you happen to be a journalist and happen to be able to spend the time on the subject that it needs. There is only one other subject that is very close as well and I’m thinking about a book about that now. That was when I was working for Spiegel Television when the wall came down. We made a lot of stories in the weeks and months after the fall of the wall, a lot of stories, and documentaries. I was editing them on weekends and writing the narration for that. I’ve already started to write a book about that time, but mainly about my own experience of that time."

- Finally libraries. We’re asking all writers what libraries mean to them or to share some library experiences.

- “That’s the memory of the world – so libraries are very, very important. I was working for Spiegel magazine for 13 years and the main asset Spiegel has, except the people working there, is the archive. The archive is a library – nothing more and nothing less – with newspaper articles and a lot of books. So I never had to go to public libraries because we had our own. If I needed a book we had it. Libraries are very important.

- I point out that a lot of media organisations are shying away from libraries – Aust anticipates my question and jumps in:

- “Because they think everything is accessible on the internet. In a certain way it is true. It is much easier to do any research today as a journalist when you have your internet access, but nevertheless this stuff must come from somewhere, and where does it come from? The internet is not an asset itself. The real thing is the book.”