Christchurch like Motown, poet says

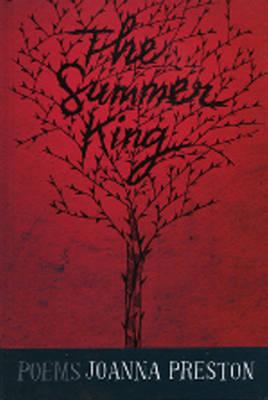

Christchurch poet Joanna Preston has recently launched her first collection. The first-ever winner of the University of Otago's Kathleen Grattan award, Preston is an Australian living in New Zealand who describes herself as a "tasmanaut".

Ahead of her performance with Frankie MacMillan at the Central Library on Friday, she spoke with Richard Liddicoat about daily visits to her bookcase, the vagaries of the writing process and why she calls Christchurch the Motown of New Zealand poetry.

- Joanna – You’ve launched The Summer King in all its glory – how do you feel now the fanfare is over? What’s it like to have the copies in your hands – or to see someone reading your work?

- It still feels quite unreal. Tragic admission time – for the first couple of weeks after my copies arrived, I made a daily visit to the relevant bookcase to say good morning to them. (They’re snuggled in between Jenny Powell-Chalmers and Helen Rickerby, and look mighty fine!) Now I’m capable of passing the bookcase without running my fingers across the spine every single time … I’m still waiting for the first casual sighting of the book in a stranger’s hands. I’ll keep my eyes open.

- A snappy description of your work was "fine and fierce" (Gillian Clarke). Give us another couple of three-word descriptions of The Summer King and tell us why you think they’re apt.

- Why does the phrase "enough rope" come to mind? Sexy and satisfying? Friendly and fulfilling? Accessible and intelligent?

Jokes aside, I would hope for "memorable and moving", maybe "tough and true". One of the things I've worked hardest on is checking the 'be nice!' reflex that my mother spent years instilling in me. Because you can’t write a powerful poem without putting those considerations aside. The poem has its own truth. - The book blurb says the Venery sequence was inspired by collective nouns – names for groups of things. That sounds quite dull, but trawling through our list for groups of animals, I’m sure that’s not the case. What made you so interested in these types of words?

-

I came across a list of them in the back of my trusty Oxford Reference Dictionary. How could any writer walk away from something like “a superfluity of nuns”, or “a host of sparrows”?

They’re so quirky, and seem so true to the nature of the animals and people. They give you an entirely new lens to look at the world through. And not just because of what they say about the animals: they tell you a lot about the people who coined them too. I’m still toying with “A Kindle of Kittens” and “An Array of Hedgehogs”.

- How did you discover your interest in words? Bonus points if you read the dictionary.

Sadly, I do read dictionaries. Dictionaries, cornflakes packets, instruction manuals … I once heard that a writer can be defined as someone who can never look up one word in the dictionary. Very true.

I grew up in a family of book lovers. My grandmother was an English teacher, and taught me to read when I was quite young. So while other kids were getting Barbie and GI Joe dolls for Christmas, I was getting books. Bliss!

- James Norcliffe said in an interview: “what a poet does is try and find out what really happened, or what it really meant” – do you think that applies to your work?

I suspect it’s true for all writers. For poets I’d add “and what it sounded and felt like”. It’s about trying to find a way of preserving a moment or an experience so that it can be accessed again and again and again, by anyone who reads the poem. And you rarely know the full story before you’re finished. (According to Robert Frost, it’s important that you don’t – “no surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader.”)

It’s one of the reasons why writing is such a buzz – the poem has very definite ideas about what is going to happen, and doesn’t bother sharing them with the writer beforehand. All you can do is hang on, and try to make some sort of sense of it all afterwards.

Jump to part two.

Poems from The Summer King

Cowarral

i Daybreak

From my bed on the back verandah

white-stippled paddocks reach

all the way to the mountains.

Frost has etched the lines

of cobwebs into the brittle air.

The sway-backed mare drowses

surrounded by wraiths of breath,

each long eyelash tipped

with a bead of moisture –

its own sliver of sun.

A kookaburra scrapes his beak

along the low branch

of the old persimmon. Soon

he will throttle the stillness,

and thaw this silver morning.

Venery

i The Pride of Lions

But before we could marry, he became a lion –

thick pelted, and rich with the musk of beast.

The switch to all fours was not easy – all his weight

slung from the blades of his shoulders.

His deltoids knotted like teak burls,

and I burnished them as he slept.

Burrs matted his mane, and for days

he wouldn’t let me groom him –

slapped me away with a suede paw,

snarled against my throat.

He would not eat fruit, or drink milk,

but tore meat from the bones I provided.

His claws caught in the carpet,

so I stripped the rugs from the floor

and polished the boards until they gleamed

and rang with the chime of his nails.

I stroke his saffron hide

and tangle my fingers deep in his ruff,

draw him up around me, ardent

as the gleam of his topaz eyes

– the hypnotic lash of his tail,

the rasp of his tongue on my thighs.

- You’ve said that music and rhythm is important to you in a poem – are you musical?

-

Yep! I played clarinet in my high school concert band, and studied singing for a few years. I can get a tune out of most instruments, given time (and possibly a soundproof rehearsal room …)

Also I have a habit of assigning a theme song (or songs) to poems as I write them … try reading The Pride of Lions while listening to Lou Reed’s song Ecstasy. Or Lighthouse-Keeper with Possente Spirto from Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo in the background.

- If rhythm is the thing that makes a poem sing, do we need a written version?

Interesting question. I’d say definitely yes, but the reasons depend a bit on who you mean by “we” – the writer, or the reader?

I know of poets who compose virtually the whole poem in their minds before ink ever touches paper. And a memorised poem is a wonderful thing – Don Paterson argued that a poem is the only piece of art that you can carry with you perfectly in your head. But there’s also something very satisfying about the physical act of writing.

I actually think better on paper. And it’s easier to revise and edit if you can see the work in front of you. The poem on the page is certainly a more intimate connection between writer and reader than the poem declaimed to an audience. (Although not necessarily more intimate than the poem whispered across the pillow, or through a candle flame at dinner …)

- You’re a blogger – tell us how technology is part of your working and writing life.

The internet is the bane and boon to end them all. It’s a great source of information, but it’s also an incredibly potent distraction. It’s a bit like the thing with dictionaries and only looking up that one word that you intended to check …

Creating a poem is often thought of as a mysterious process – You’ve said for you its about craft and technique. Do you chisel poems out or do they just leap in your mind like mashed banana?

Creating a poem is often thought of as a mysterious process – You’ve said for you its about craft and technique. Do you chisel poems out or do they just leap in your mind like mashed banana? Mashed banana? Remind me not to invite you over for breakfast!

It’s a bit of both. Sometimes you’ll get a poem almost fully formed – call it a gift of the muse, call it a payoff from your subconscious mind for hard work elsewhere, call it luck. But there’s almost always something that can be done to make it better.

Simple mechanical things, like shifting a linebreak to weave in a possible secondary meaning. A verb that could be stronger. Maybe the sounds aren’t quite right – the poem wants to be sly and secretive, but you’ve used words that have harsh, aggressive sounds.

Even if the poem is perfect as it is, going over it critically teaches you a huge amount. Gets those sorts of skills ingrained, so that your subconscious mind does most of the editing as the poem flows out of the pen, and you can fool yourself into thinking that the poem “just came”.

But I still don’t really know what it is that starts the poem. What it is that gives it life. You write and revise and read and write, and keep your fingers and any available organs crossed that somewhere that spark will happen, and the part of you that you only borrow will take over and make the words into a proto-poem. You learn ways of enticing it; of making it more likely to happen. But you can’t control it. It’s why writer’s block – the real thing, not just the bored “I don’t really want to do this today, ooh look, a chaffinch!” self-distraction version – is so terrifying.

- You won the Kathleen Grattan award, a sum of $16,000. The Poet Laureate in New Zealand is also a hefty sum ($50,000) it seems that it’s a good time to be a poet! Tell us about the health of the local scene.

Hmm. Unfortunately cheques like this are fairly uncommon. From a financial point of view, things aren’t good at all – the New Zealand Poetry Society for example has had their funding completely cut.

But the Christchurch poetry scene is actually pretty vibrant. The Canterbury Poets Collective have the longest-running poetry readings series in the country, and this year’s autumn readings series was standing room only on every night. Cantabrians dominate the NZPS poetry competition – last year at the Wellington launch of the anthology, it seemed like most of the people in the room were from Christchurch. And this year we’ve been so successful that they’ve decided that the launch should be in Christchurch instead!

The Hagley Writing course is looking really exciting, and we have poet after poet bringing out new books … no matter what you like or don’t like about poetry, there’s someone (usually a group of someones!) writing and performing and publishing exactly what you’re pining for. Christchurch is the Motown of New Zealand poetry.

More information

- Read more about poetry at the library

- Joanna Preston's blog

- Kathleen Grattan award for poetry

- Canterbury Poets Collective

- Catalyst

August 2009