Junot Diaz — interview

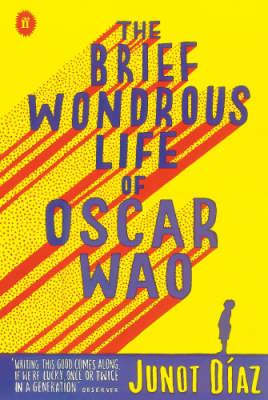

Junot Diaz is a rock star in the world of literature. The brief and wondrous life of Oscar Wao is a complex and multi-layered book mixing Spanish and English, dictatorship and freedom, history and now, sex and geekery. This intriguing and talented author spoke with Richard Liddicoat during the Auckland Writers and Readers Festival 2008.

They say what you don’t know can’t hurt you.

They is wrong. And they is right.

My research about Junot Diaz consisted of all the usuals — reading the author’s work, finding online information such as watching him reading at the Google campus and listening to online interviews. I knew about fuku - the curse that always gets its man, I knew about Trujillo — it was all good.

Festival appearance

I went to Friday night’s session with Diaz, chaired by Guy Somerset, feeling prepared. My interview was the next day I could relax and enjoy. The only complicating factor was Kim Hill, who was interviewing Diaz immediately prior to me. I hoped if she fried him, he would fry her back, be the incredible comeback man, spray inquisitor repellent, or fire the anti-everything ray and still be in superhero mode when he came to talk to me.

But my research hadn’t factored in any new information. Diaz revealed during the session a childhood love of New Zealand and our culture; he is also a fan of New Zealand director Martin Campbell’s Edge of Darkness. Campbell later directed The Professionals and Bond movies.

Diaz went on to say that he loved Margaret Mahy as a young reader. I can’t lay claim to being a librarian, but as an employee of Christchurch City Libraries it is my sworn and solemn duty to simultaneously jump for joy, yelp and faint when a rock star like Diaz mentions her name. She is New Zealand’s Greatest Living Talent, a precocious and wickedly inventive imagination, a conjurer of astonishing power, our very own superhero. I invoke standard procedure.

To the 28th floor!

Next morning I pick my Junot-mentioned-Mahy post-swoon self up, dust off my standard issue find it 24/7 T shirt, and lug the mics and my anything-but-superhero-feeling butt up to the Crowne Plaza. We end up on the 28th floor, where Sarah Hall and Thomas Kohnstamm — other authors at the festival — are steeling themselves for another day on the circuit with guests and cheerful breakfast conversation.

Rolling the tape, (which just sounds so much rock n roll than initiating the record mechanism on the solid state digital device) I welcome Diaz, who says:

I cross my arms with the double devil sign.

I trust my instinct that this is good, and lurch into a question about how the connection to New Zealand came about from a young Diaz’s urban New York.

Island people; I’m an island person just an accident of …

He changes tack, like island weather.

Well look; what made immigration so interesting for me is that four of us siblings emigrated and if you look at us as children what was really fascinating was that some of us kept travelling. We just kept reproducing that experience.Even when I was little I wanted to read about different places. The first country I fell in love with was Mongolia. Strangely enough I read the books of Roy Andrew Chapman, the prototype for Indiana Jones, the archaeologist guy who found the dinosaur eggs in the Flaming Cliffs. As a kid it was my first experience of the outside world.

I was so desperate to understand how I came to America that was looking for histories and I was looking for models of other people that were travelling. New Zealand was country number three I discovered.

Happy accident

Margaret Mahy was a random and intriguing choice:

I discovered Margaret Mahy completely by accident by pulling a book from a library. I said oh, this persons from New Zealand. I’d never heard of it.

Something was sparked and he followed. He wanted to know everything.

I’m such a completist, I just dove into it. The first book of hers I read was The Changeover. The character is half Māori, or might be because she doesn’t know who her father was. I didn’t know what half Māori could have been.

As a kid I always assumed if I didn’t know it it was because of my immigration not because it was a fact that had to be discovered from outside. I assumed every American knew what a Māori was and I was the only fool who didn’t because I was from abroad. As a compensation I would dive into this stuff to try to learn all about it. It really started from there.

Then a couple of years later the Edge of Darkness was showing and in some ways it was like the circle was complete. It became closed; I realised that this was something that was existing in my imagination in a powerful way.

Disappearing cultural rhythms

Edge of Darkness is an apocalyptic environmental drama from the 1980s BBC. Intense and gripping in a way the BBC do better than anyone else it was a long slow burner of a tale. Diaz says the style and the rhythm of that type of storytelling has disappeared.

You know when they talk about language disappearing and cultures disappearing and patterns, even like local businesses being wiped out by big chains; one of the things that’s also been wiped out is rhythms. Watching that movie is a rhythm from the 80s where people were more willing to wait six, eight hours to get a payoff. That rhythm has disappeared. I try to show that movie to people who don’t remember that earlier rhythm and they don’t get down. They can’t get down at all.

Distractions are invitation to other books

Rhythm, or competing rhythms are very much a feature of Oscar Wao, where the footnotes and different voices and points of view are used to distract the reader away from the main story into other stories. The footnotes compete for your attention with lively asides, like flash fiction set into the space of the main story. (When I say distracting I mean it profiles well-hung womaniser Porfirio Rubirosa, science fiction geek-outs, and short historical biographies of torturers in the Trujillo regime.)

Rhythm, or competing rhythms are very much a feature of Oscar Wao, where the footnotes and different voices and points of view are used to distract the reader away from the main story into other stories. The footnotes compete for your attention with lively asides, like flash fiction set into the space of the main story. (When I say distracting I mean it profiles well-hung womaniser Porfirio Rubirosa, science fiction geek-outs, and short historical biographies of torturers in the Trujillo regime.)

There is another outcome though the non-academic style of footnotes push you towards other sources, more reading, more questions and the feeling that your knowledge has been found wanting. Diaz continues:

If you’re interested, this is a book that invites you to other books; that directs you to other books. Its a book about authority on every levels. The best way to guarantee authority is to have the book hermetically sealed. What that means of course is that if its the only book that survives, its the only book that we have.

What I always loved, as someone whos trained in history, was that books even fragments of books would mention books that we don’t even have any more. That at least gave a context that there was a discussion between texts.

Tyranny of the master narrative

The idea of a master narrative scares the hell out of me. As a child of the dictatorship of course its going to scare the hell out of you. And so whether it was the footnotes competing with the narrative of the master overtext; whether it was that the book countered its own authoritativeness by directing you to other books on the same theme, competing books … The average author wants to devour the territory.

They don’t want to say to you go and read these x books that might be even better than mine on the topic and make up your own mind. It’s taught to you that you should studiously ignore the competition.

I’m scared of that because those lessons were the lessons that we learned in this kind of post-dictatorship / dictatorship-traumatised country.

Not only because I love books and I want to encourage people to read stuff that I was deeply moved by, that would me gain metaphors and lenses through which to interpret the world, it was also the desire to change the way that we read.

The way that I was taught to read is that the text, while you were reading it is sacrosanct and one.

That was the national myth of the Dominican Republic as long as this story’s going on, this story is sacrosanct and the only one. Competing narratives were dismissed, marginalised — they were assassinated. It might be an extreme pretentious jump between reading and dictatorships, but I couldn’t get it out of my head

Is Diaz like Spike Lee?

I bring up a comparison mentioned on Scoop to the film work of Spike Lee. Diaz is undoubtedly creating new language and expressions and stylistic elements, putting his take on things out there. I asked of there was an element of a if you don’t like it, hard luck in the approach. There wasn’t.

I think it’s being misread — not the book, the strategy. People assume that if you deploy language or themes or illusions that are not general or not mainstream that there’s an aggression to that. I actually don’t think that I use these references because I’m like well if you don’t get it, tough luck. I am an immigrant; I am a product of if you don’t get it, tough luck.

In my case that wasn’t at all what I was thinking about. I always thought that the idea was that if you encounter something in a book that you don’t understand, what’s great about a book is that you can fold the page.

I could never fold the page on a [real-life] moment that I didn’t understand and go to someone else and say hey could you explain that moment to me? That was impossible.

The wondrous thing about a book is that it allows you to hold your question about whatever it is that you are reading and then when you’re done with it approach someone else it sort of invites you to go out and get some explanation. I always thought that the hermeneutic quality of the book was an excuse for readers to build community not to remind them of their isolation, to remind them of their limitations.

Everything in our world does that and does it better than a book could. I wasn’t interested in that. I really wanted people to ask each other questions. Look, nothing is funnier than the image I have of our mother, who knows all the Dominican stuff inside out, forced to ask my little brother who the Fantastic Four was. I loved that.

The communities and ages have to talk to each other in my utopian dream of the power of the book. Thats what I was hoping for the collectives that never had anything to do with each other would be forced in some ways to commune.

However particular a book is, it invites you to seek, in some way, assistance. A particular is always going to elude us and requires collective to understand it, while the general can always be understood by the individual.

So where’s the laugh track?

At this point my head is nearly exploding. None of my research could have made me prepared — Diaz has been studying this thing for 11 years. He is professor emeritus — I finished the book the night before. I point out a line in the book that reads: You can start the laugh track anytime now. With all the heaviness of dictatorship, authority, grappling with language and different points of view, the storytelling has a rich vein of humour. I was intrigued by this mix. Diaz said he aimed high from day one.

I set up these aesthetic challenges from the start. Can the sci-fi madness of Oscar exist with the traditional historical novel? That was one of my challenges. And can this book be the funniest book and also be the most horrific and scary and heartbreaking? And can it be simultaneously these things without one erasing the other?

The third challenge was could it be a book that at every moment is of the now? At every moment it felt like a contemporary person was speaking to you? Could it really be honest to be what it means to attempt to reach back into history? Could it be, in some ways, super-hip, but also incredibly canny about the historical and about informational rescue missions?

From the beginning these were little patterns that I charted to myself. I said Can you do this? Because if you can’t do this, then a book like this, for me, wouldn’t have been worth it. It was the aesthetic challenges that defined what’s fascinating about the book.

New York conversation

Characters were less important in meeting his writing challenges. He tells me this in the most famous of the New York/Pacino/De Niro-style conversational methods the rhetorical question with expletive included.

Characters? We know characters. We’ve seen beautiful characters. Characters we can connect to? Everyone can do that. I could do it but the only thing that will keep you going for 10 years is if you create these minor challenges for yourself, otherwise, f*** those 10 years are going to be miserable.

And make no mistake, Diaz was miserable during that time. I mention an interview where he found himself almost at the top of the bridge.

I didn’t almost find myself. I found myself. My girl’s over there, she could tell you about my bridge moments.

A never-ending story?

I ask him some mangled, try-hard question about the writer’s solitary life coupled with a lame kind of life-on-the-28th-floor-touring-must-get-boring vibe, but he goes back to the top of the bridge. It’s a place he knows well.

A part of what defines my character is that I’ve never left the bridge. No matter how much people go I like that, or that was a wonderful speech, I spent a decade of failure just failing. Watching students of mine publish books while I couldn’t put it together. I never got off that, It defines so much of what I do.

I can enjoy myself; I’m having a brilliant time here, but in the end the applause the little of it there is never erases the fact that I know what it means to be in a f***ing hole. For a very long time. I guess that’s who I am.

But there’s a part of me who knows that but for the grace of God for accidents of skill and convergence this book would have never f***ing finished.

In other words once youve already started down the path, as they say, in for a penny in for a pound. You’ve already started it, so you might as well see it to its horrible conclusions and spare someone else that. Its like you’ve been assigned your corner of hell to map and if you fail mapping it, theyre gonna send someone else. Someone else will be summoned.

Even if you’re going to be reduced to a cinder, its the least you could do — you already got you’re feet burned.

Part of me was like proletariat solidarity; I must do my assigned task silly, silly immigrant shit.

Academia: another on the same

Diaz had done many jobs, steel mill, pumping gas he likes to surprise his girlfriend with new places he used to work, but now he teaches creative writing at MIT. I asked how he fitted in to an academic environment.

The steel mill I worked in had quirkier characters than any department I worked in. In some ways I’ve been very fortunate in this regard I was recruited to teach, which is less a sign of talent that a sign of their need. I’m not saying that as some kind of throwaway modesty both institutions needed to fill positions quickly. And when they hire artists, as long as the artist keeps producing and doesn’t abuse anybody they tend to give you a lot of leeway.

As a person of colour in the United States, its as if the mainstream doesn’t really know what the f*** you’re about, or what the hell you’re doing or why you talk this way. You say stuff or you do stuff and theyre kinda waiting for the joke, even though you’re being serious. And theyre waiting for the joke for four or five years. Academia its like the poets put on their subtitles another on the same. It was just another American experience for me.

I wouldnt say that I’m an academic. At all. I don’t think my colleagues would say it either.

Free Armani for the rest of your life

We had decided to ask most of our interview subjects about libraries, and if he wasn’t a rock star before, Diaz won himself a librarian army when he said:

Libraries are a weird thing if you actually think about it. It’s sort of like the logic of capital minus the logic of capital. Its a place where you can get books for free and as long as you bring them back everything’s cool.

Could you imagine a clothing cultural component like that? Where you could, as long as you orderly waited and wrote your name on a list, rent out an Armani suit in brand new condition and just wear it and bring it back?

Both are products, its just an accident of history that weve attributed one a cultural component and the other not.

For a poor kid a library to me was as like a miracle to me as if you discovered if you could sign your name and take out a whole wardrobe of Armani clothes. Every day. For the rest of your life. That’s what a library felt like.

The assured, velvety-smooth drawl went on as whatever song the librarian army would sing was turned up to 11 on the old rotary dial stereo in staffrooms around the nation.

I never understood the image of librarians in popular culture. Old, sort-of doddering every librarian I ever had was incredibly young, energetic and hip even if they were 60. And would take their time for this snot-nose kid from the Dominican Republic to guide them to texts.

Everyone has this idea of the valiant archetype the scout who leads you through the new land. New Zealand has that, the myths of all their like pioneers; Australia, the United States.

>In the end, the only forest really worth being led through is the forest of the mind, books. In a sense librarians are these incredible scouts for this inner frontier. No-one views it as that but for me it was more important than anything having those kinds of scouts who would guide you.

The dream of the unwritten book

Interviews are a weird way to meet people most of the time. You ask them to tell you a story, so that you can tell that story to someone else. You get paid to do so. It can feel like your are rummaging through their drawers, or rifling through their wallet as you take little snippets of lives and tell other people about them.

Sometimes you get gifts that astonish you, words or revelations that you would have to double cross the devil to get. The devil might come after me, so read this quick — it is payback for all the times you’ve helped someone by the simple act of giving them a book.

Everybody makes a living in the arts world off playing up how rough and how tough and how loveless and how edgy their lives were, Diaz went on.

Mine was as tough as the next person; it wasn’t a fun time. Librarians were the one utopian constant in a world that has no utopian constants. It was the only gift that I still dream about.

I keep my mouth firmly shut, not knowing what was coming.

There’s not a night that goes by that I don’t dream that I’m in a library and I find a book that’s never been written — a new Melville novel, a new Toni Morrison novel. In my dreams I always wake up when I check the book out. I have these dreams non-stop.

Junot Diaz, rock star and superhero, I cross my arms with the double devil sign. Your suits are due back next Tuesday.

More on Junot Diaz

- Books by Junot Diaz

- Opinion: Literature opens the door to compassion in our brief lives, Sydney Morning Herald, May 26 2008