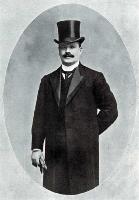

George Samuel Munro, 1864-1915

Mr G. S. Munro was not a “local” but due to his involvement with the 1906-07 International Exhibition held in Christchurch he became a prominent and highly publicised personality of the time.

On 23 November 1906, the Christchurch Star reported on the behaviour of Munro, who at that time was the Exhibition’s general manager. He had, they wrote, behaved “passing well”

during the previous week; apart from “a little grievance with the visiting firemen, a difference of opinion with the director of entertainments and several little passages-at-arms with the Press and Pressmen”

1, he had not bothered anyone. His health, they concluded, must be failing! This sarcastic comment was typical of those fired at Munro during his time in Christchurch; he was the man whom local people and the local press loved to hate.

Everything he did was wrong. He lacked “the tact and ‘savoir faire’ which are absolutely essential to the discharge of his duties”2

. He was “exceedingly arrogant”

3, lacked “breeding and refinement”

4, was “rude to all and sundry”

5 and, all in all, had “a nasty way with him”

6. His “chronic temperamental disorder”

7 meant he was quite unable to work in harmony with his colleagues and in any case, he believed “in his own autocracy as fervently as if he were the Czar of Russia”8

. The New Zealand free lance reported that “Tom” Wilford immortalised himself by studying the royal arms and motto “Dieu et mon driot” which adorned the Exhibition entrance, and then announcing it should read “Dieu et Mon-ro!”9 Needless to say, Munro’s decisions were frequently unpopular; The Press could not decide whether his “cheap appraisements or his tasteless disparagements [were] the more offensive”

10.

George Samuel Munro was born in Invercargill in 1864, the son of auctioneer John Munro. The family moved to Westport in 1867, where John Munro became active in public life, serving five terms as mayor in the 1870s and representing Buller in the House of Representatives from 1881 to 1884. George Munro was educated in Westport and then joined his father’s firm, a general merchant and auctioneering business which also acted as agent to a number of insurance companies. In 1890, he moved to Dunedin where he joined Fulton, Stanley & Co., shipping agents and wool and grain merchants. He became the firm’s manager in 1894. After an unsuccessful mining venture back on the West Coast, Munro joined the Department of Industries and Commerce in Wellington in 1902, and was appointed Acting Secretary during the absence of the T.E. Donne at the St. Louis Exhibition in 1904. His appointment as full-time Executive Commissioner to the New Zealand International Exhibition followed in November 1905, his wide business experience cited as being very advantageous.

The organisation of the Exhibition was a huge undertaking, and it was not made any easier by the number of committees established for the purpose. Mr C.M. Gray noted in November 1906 that 320 people had sat on the general committee and 32 on the executive committee, with a further 254 on the 23 sectional and 51 sub-committees Over 850 meetings were held in the months leading up to the opening of the Exhibition. Fierce parochialism seems to have shaped the proceedings from the start, with local businessmen and other representatives bitterly resenting the control imposed by the man from Wellington. As the New Zealand free lance suggested, Munro may have lacked tact and spoken his mind too brusquely as he stubbornly defended his decisions, but he soon became “the unfortunate scapegoat for all-round attacks, as fair game”

11 in the undignified squabbles aired in the press, many of which involved the “pettiest puerilities”

12. Not even the local newspapers denied that he had a “keen instinct for industry and an excellent capacity for getting subordinates to work”

13, or that the practical success of the Exhibition was in great measure due to his efforts.

Nevertheless, in November 1906, after the exhibition opening, the Government was forced to step in and mediate between Munro and local commissioners, W.Reece and G.T. Booth, who, like Allan before them, were threatening to resign. It was decided that the Minister in charge of the Exhibition would accept full responsibility for all final decisions, but Munro’s practical good work was acknowledged by his appointment as general manager. In fact, Munro’s role can hardly have changed, but faces were saved by the creation of the new title, and the locals, already buoyed by the Exhibition’s success, pronounced themselves happy with the new management arrangements. Criticism of Munro’s behaviour, however, continued in the press, and he certainly seems to have quarrelled with almost everyone over the next few months. He himself claimed that he was just and consistent throughout, and always did what he thought was right, without fear or favour. Perhaps, as the New Zealand free lance suggested, his flutter “for a brief spell on the stage of fame …[as] the most celebrated as well as the most feared person in the Dominion”

14 was simply too much for “a relatively modest violet under the sweet hedgerows of the Tourist Department”

.15

Munro married Mary Jane Helena Theresa Loubere of Ahaura in 1884. His children were educated at least partly in England, his son, Roy at Bedford School, and his daughters, Mabel and Emmie in London, where they studied music. By 1906, both girls had established successful stage careers with the Gaiety Company, which performed musical comedies. Later they joined George Edwardes’ Comic Opera Troupe. Early in 1908, Munro and his wife sailed for “Home” themselves, and by January 1909, they were settled at 19 Aughton Street, Birkdale, Southport, in a house they named Haeremai. Munro was employed in nearby Liverpool by one of the largest meat firms in the west of England. He died at his home on 17 August 1915.

Footnotes

- 1. Christchurch Star, 23 November 1906, pg. 4.

- 2. “The latest ‘Munro Doctrine’”, The Press, 30 October 1906.

- 3. “The latest ‘Munro Doctrine’”, The Press, 30 October 1906.

- 4. “The latest ‘Munro Doctrine’”, The Press, 30 October 1906.

- 5. New Zealand Truth, 10 November 1906, pg. 6.

- 6. New Zealand Truth, 10 November 1906, pg. 6.

- 7. Editorial, Christchurch Star, 15 March 1907.

- 8. Editorial, The Press, 30 October 1906.

- 9. New Zealand free lance, 24 November 1906, pg. 1.

- 10. Editorial, Christchurch Star, 15 March 1907.

- 11. New Zealand free lance, 17 November 1906, pg. 6.

- 12. New Zealand free lance, 17 November 1906, pg. 6.

- 13. Editorial, Christchurch Star, 2 November 1906.

- 14. New Zealand free lance, 15 February 1908, pg. 5.

- 15. New Zealand free lance, 17 November 1906, pg. 1.

Sources

- Christchurch Star, 23 November 1906, pg. 4.

- Editorial, Christchurch Star, 15 March 1907.

- Editorial, The Press, 30 October 1906.

- “G.S. Munro”, The Weekly press, 31 Oct 1906, p. 39.

- “Mr. G. S. Munro”, The Press, 1 November 1906, pg. 8.

- “The latest ‘Munro Doctrine’”, The Press, 30 October 1906.

- New Zealand Truth, 10 November 1906, pg. 6.

- New Zealand free lance, 17 November 1906, pg. 1, 6.

- New Zealand free lance, 15 February 1908, pg. 5.

Discover your family’s history at our libraries

Discover your family’s history at our libraries