Maria Thomson 1809 - 1875

Maria Thomson

Weekly press: jubilee number, 15 December 1900, p98

When establishing its settlement, the Canterbury Association laboured mightily to include among its attractions a fee-paying high school for the sons of the well-to-do. Little consideration was given to the possibility that the daughters of the prosperous might seek a similar boon and thus there was no provision for a Christ’s College for girls. Nevertheless, the upwardly mobile did demand a high school education for their daughters and it was Maria Thomson who filled this gap in the market.

In December 1852, at Gravesend, Maria Thomson, 43, boarded the Lyttelton-bound vessel Hampshire. She did not quibble at the fact that, for six weeks, winds confined the ship off the coast of England:

“In the placid beauty of calm weather and the awful grandeur of the storm - in the boundless roll of the ocean and the glorious expanse of the heavens - I feel an intense worshipful admiration and a peaceful enjoyment far more perfect than usually falls to the lot of any on the busy land.”

The Hampshire finally reached its destination on 6 May 1853. To Maria it was of the utmost importance that she find, in Canterbury, “a happy and prosperous home”. Although from a cultured background and experienced at teaching the daughters of the well-heeled, she had suffered “great vicissitude … and unusually sharp trial”. Whether her husband, Charles Thomson, had contributed to these problems is uncertain. It is clear, however, that, in an age when a woman’s persona was absorbed within that of her spouse, Maria was an extreme conformist. In her advertisements, even in her death notice, she is Mrs Charles Thomson; only in land records and her will is she Maria. Yet when she arrived in Christchurch, she was already a widow.

Maria purchased, for £220, parts of Town Sections 1047 and 1049, a 43 perch property situated towards the western end of Oxford Terrace. On this site, on 22 March 1854, she opened the “Christchurch Ladies’ School” in a building called “Avon House”. The school, which catered for day girls and boarders, subjected both groups to a well organised regime. Boarders had hair brushing for eight minutes, both night and morning, and twice each Sunday, trooped off to divine service at St Michael’s. An honour much sought after by younger pupils was that of carrying the lamp which lit the path at night. Maria’s curriculum included the genteel female accomplishments - pianoforte, guitar and singing - but other disciplines included writing, arithmetic, English, drawing and a strong dose of foreign languages - Latin, French, German and Italian. The pupils’ limited spare time was spent in picnics and simple games, of which hopscotch was a favourite.

The surnames of Maria’s pupils are a roll-call of families who were climbing or already at the top of the greasy social pole - Boag, Alport, Brittan, Ollivier, Mathias, Moorhouse, Deamer, Caverhill, Miles, Coward, Barker and Gresson. Doubtless each girl learned the skills needed to manage a large household and a socially prominent spouse. But there were problems. Infections spread quickly in crowded classrooms and bedrooms, and, sometimes, there emanated from the school an overpowering smell of disinfectant.

One pupil, Mary Brittan, sought to stage a farce, the Old maid. Alas, of the eight characters, five were male. Maria vetoed a scheme to have, in the male roles, either young men or girls dressed in trousers. Instead a reluctant Mary organised a game of charades. Mary Brittan was, however, a pupil on whom Maria would smile. She married William Rolleston in 1865 and, three years later, he became Superintendent. As first lady of Canterbury, Mary was an unofficial but charming and effective bulwark of the Establishment.

While “Avon House” would, for several generations, be “a very comfortable looking cottage”, it had but a short life as a school. Between 1858 and 1860 Maria purchased Town Sections 115 and 116, “fronting Antigua Street and Salisbury Street”, and 117 and 118 which fronted Antigua Street; today they would be described as on the Park Terrace-Salisbury Street corner. The school was ensconced on this one acre site in a “large, two-storeyed, timber house”. An 1862 Lyttelton times report stated that, on Papanui Road, builders were erecting for Mrs C Thomson a girls’ school-cum-dwelling place, a “very large and handsome house … decidedly the largest private house in or about Christchurch”. The project was abandoned. Maria’s second school would eventually become the town house of landowners Joseph Hawdon and William “Ready Money” Robinson.

Having been persuaded by friends “at Home” to return to England, Maria announced that she would close her school “at the expiration of one year, dating from midwinter 1863”. However, her departure was delayed. In 1864 she had a “ladies school” on Town Belt East (FitzGerald Avenue) and, the following year, at Avonside, taught working class children. The parents paid so that their offspring could attend an Anglican primary school, which was part-funded by the provincial government.

After visiting the 1865 New Zealand Exhibition in Dunedin, Maria travelled through the country to Auckland. The Queen City, with its “monotonous never-ceasing down-pouring of rain”, was the “dullest place on earth”, though parts looked well from the deck of an Australia-bound ship. Melbourne, Adelaide, Ceylon, Aden, Suez, Alexandria, Malta and Marseilles - these were stopping-off points on the way to the United Kingdom.

Maria haggled with boatmen in Egypt and took in the usual - and unusual - sights. She appreciated how, in the Melbourne Cemetery, the boundaries of the various denominations were marked by simple pathways. A pure white monument bore the Christian names and dates of birth and death of three children who had not lived beyond one year; there was “something very affecting in this simple and elegant record, without a comment or superfluous word, without even the names of the bereaved parents”. In England, Maria edited her journal which was published, in 1867, as Twelve years in Canterbury, New Zealand.

The school mistress soon succumbed again to the call of the Antipodes. By 1868 the Glenmark had brought her back to Lyttelton and she was placing her restrained advertisements in Christchurch newspapers. Till 1875 “Mrs Clark [and] Mrs Chas Thomson” operated a school in Maria’s old stamping ground, Oxford Terrace. It is probable that Maria was in charge of academic subjects. A kindly soul, Mrs Clark had previously run the Richmond House Seminary for Young Ladies, teaching girls to “sew, read, write and do their sums in that order”.

One of Maria’s friends was the Rev Henry Jacobs. The second Mrs Jacobs, Emily Thompson, had been an “Avon House” pupil, and her sister, Mary, was on the staff. Jacobs described Maria as having “a vigorous… almost masculine mind… strong good sense… [and] acquirements and accomplishments of no mean order”. Away from the school situation - in which she was known as the “great moral engine”- she showed “true kindness of heart… feminine tenderness… and … lively sense of humour.” Jacobs listed the distinguishing points of Maria’s character as conscientiousness, love of truth, genuineness, consistency and an unostentatious but deep and fervent piety.

Maria was an active businesswoman. To upgrade her school and pay for trips within New Zealand and to the “Old Country”, she found it necessary to mortgage her properties. Sometimes she dealt with friends including Judge Henry Barnes Gresson (father of an “Avon House” girl), the Rev William Fearon and the Church Property Trustees. Businesses with which Maria associated included the Permanent Investment Loan Association and New Zealand Trust and Loan Company. In the former she held shares; the latter was linked to the cautious well-established Union Bank of Australia. Others with whom Maria had a commercial relationship included the genteel Torlesse family, prominent bureaucrat John Marshman, and shrewd businessmen Richard Harman, Richard Packer, Joseph Hawdon, and George and Robert Heaton Rhodes. Maria was a good credit risk, had an interest in a large amount of land and held mortgages over the property of working class people to whom she loaned money.

During her Christchurch years, Maria adhered strictly to a rule whereby part of her income was set aside for her God, His church and the poor, the details being kept separate from other accounts. As she grew older, she pondered on “the mysterious future… the changes which death would bring”. On 8 October 1875 she made her will. A cousin in England and a niece “at present or lately residing in the Boulevard de Sebastopol, Paris,” received legacies. Tosswill family members, including Maria’s god-daughter, Ellen Mary Tosswill, were provided for; so also was Mary Fereday, wife of Maria’s lawyer. Maria’s main concern, however, was that the work of the church would benefit on her demise. The residue of her estate - estimated at £1600 - was left in trust to the bishop and Henry Jacobs “to be applied to such religious and charitable purposes as they in their discretion shall think fit”.

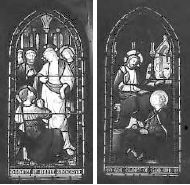

Stained-glass windows to the memory of Maria Thomson, St Michael’s and All Angels” church, Christchurch

Stained-glass windows to the memory of Maria Thomson, St Michael’s and All Angels” church, Christchurch

Maria would have been pleased that the efforts of “old friends [who were] not pupils” raised sufficient money for a memorial window in the chapel in the Barbadoes Street Cemetery, while ex-pupils easily gathered together a sum to cover the cost of two windows in the south-eastern corner of the second St Michael’s church. Designed by the architect Benjamin Woolfield Mountfort, these depicted “Christ in the house of Mary and Martha” and “Christ and the disbelief of St Thomas”. Maria would also have nodded approvingly when Henry Jacobs pumped substantial sums from the Maria Thomson Fund into the establishment and maintenance of Cathedral Grammar, both a preparatory school for Christ’s College and a place which provided free education to boys who were members of the Cathedral Choir.

Maria anticipated that she would meet a sudden end - and she did. She suffered a stroke. Jacobs came to sit with his friend and, “after a few hour’s illness”, she died on 21 December 1875. Her death notice was brief, her career and funeral ignored by the papers, perhaps at the lady’s instruction. Maria’s gravestone in the Barbadoes Street Cemetery overlooks the Avon. The death date and age of the deceased are given in Latin. Part of the inscription states bluntly:

“Here lieth all that was mortal of Maria, relict of Charles Thomson…”

Sources

- Bruce, A Selwyn. Early days of Canterbury (1932)

- Church register transcripts of baptisms, marriages and burials, Aotearoa New Zealand Centre, Christchurch City Libraries

- Ciaran, Fiona. Stained glass windows of Canterbury, New Zealand (1998)

- Clark, G L. Rolleston Avenue and Park Terrace (1979)

- Discharged mortgage files, Archives New Zealand, Christchurch

- Garrett, Helen. Henry Jacobs, a clergyman of character (1997)

- Gosset, Robyn. Ex cathedra (1975)

- Hewland, Leonard. “Girls’ schools in early Christchurch recalled”, Press, 30 April 1956

- Land Records, Land Information New Zealand, Christchurch

- Lyttelton times, 25 February 1854, 4 January 1862, 3 June 1863, 23 May 1868, 21 December 1875

- Macdonald, G R. Macdonald dictionary of Canterbury biographies, Canterbury Museum Documentary History Department

- New Zealand church news. Christchurch Anglican Diocesan Archives

- New Zealand Society of Genealogists, Monumental transcriptions of the Barbadoes Street cemetery, Christchurch (1983)

- Norman, E J. History of the Avonside parish district. MA thesis, Canterbury University College (1951)

- Packard, Brian. Joseph Hawdon: the first overlander (1997)

- Rolleston, Rosamond. William and Mary Rolleston (1971)

- Southern provinces almanac, 1863-65, 1872-1875

- Thomson, J J. Reminiscences. Christchurch City Libraries’ archives

- Thomson, Maria. Death certificate, Births, deaths and marriages, Lower Hutt

- Thomson, Maria. Research notes of P M French, Auckland, and Christchurch City Libraries’ archives

- Thomson, Maria: will, Archives New Zealand, Christchurch

- Weekly press, jubilee number, 15 December 1900, p98

Discover your family’s history at our libraries

Discover your family’s history at our libraries